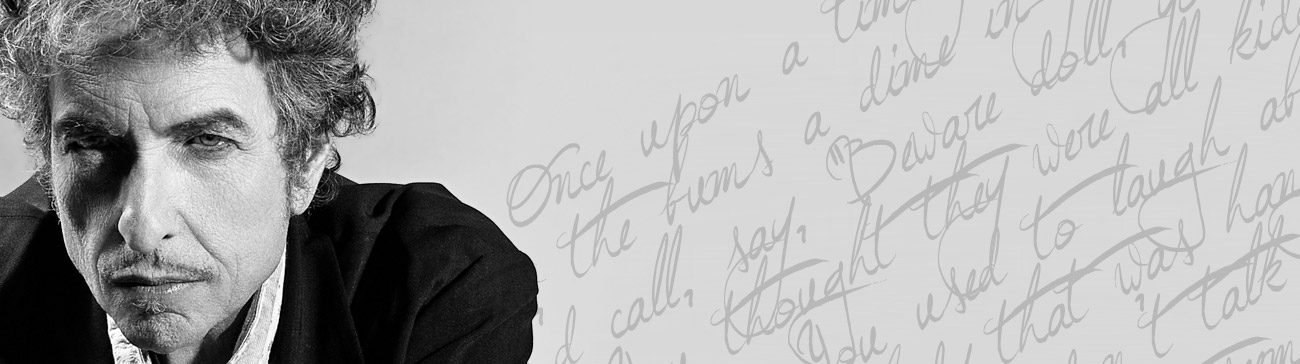

Bob Dylan

Bob joined the Buddy Holly Educational Foundation in February 2014 as a lifetime legacy ambassador with the “Think it Over” guitar

Dylan talked about Buddy Holly in his Grammy acceptance speech for “Time Out of Mind” winning Album of the Year.

I just wanted to say, one time when I was about sixteen or seventeen years old, I went to see Buddy Holly play at the Duluth National Guard Armory (late January, 1959)… I was three feet away from him… and he looked at me. And I just have some sort of feeling that he was – I don’t know how or why – but I know he was with us all the time we were making this record, in some kind of way.

Bob Dylan is the uncontested poet laureate of the rock and roll era and the pre-eminent singer/songwriter of modern times. Whether singing a topical folk song, exploring rootsy rock and blues, or delivering one of his more abstract, allegorical compositions, Dylan has consistently demonstrated the rare ability to reach and affect listeners with thoughtful, sophisticated lyrics.

Dylan re-energized the folk-music genre in the early Sixties, brought about the lyrical maturation of rock and roll when he went electric at mid-decade, and bridged the worlds of rock and country by recording in Nashville throughout the latter half of the Sixties. As much as he’s played the role of renegade throughout his career, Dylan has also kept the rock and roll community mindful of its roots by returning to them. With his songs, Dylan has provided a running commentary on our restless age. His biting, imagistic and often cryptic lyrics served to capture and define the mood of a generation.

For this, he’s been elevated to the role of spokesmen – and yet the elusive Dylan won’t even admit to being a poet. “I don’t call myself a poet because I don’t like the word,” he has said. “I’m a trapeze artist.”

Bob Dylan was born Robert Zimmerman on May 24, 1941, in Duluth, Minnesota, and grew up in the iron-mining town of Hibbing. He learned to play harmonica and piano by age 10 and was a self-taught guitarist. As a high-school student in the late Fifties, he listened to everyone from Hank Williams and Woody Guthrie to Roy Orbison and Chuck Berry, cultivating a lifelong appreciation for traditional folk, country, and rock and roll. While attending the University of Minnesota, Dylan traded his electric guitar for an acoustic instrument and began to pattern himself after quixotic folksingers of the previous generation.

In January 1961, Dylan moved to New York City, where he gravitated to the folk and blues scene on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village. He debuted at the premier Village folk club, Gerde’s Folk City, on April 11, 1961, opening for bluesman John Lee Hooker. After playing harmonica on a session for folksinger Carolyn Hester, Dylan was signed by producer John Hammond to a contract with Columbia Records. Except for a brief hiatus in the early Seventies, Dylan has recorded for and remained with the label since 1961. Near the outset, fellow folksinger Pete Seeger remarked, “He’ll be America’s greatest troubadour, if he doesn’t explode.”

On Dylan’s self-titled first album he recorded topical folk songs, accompanying himself on harmonica and guitar. Bob Dylan contained only two originals (“Song for Woody” and “Talking New York”). Made in a matter of hours, it cost $402 to record, according to John Hammond. By contrast, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, released in May 1963, was almost entirely self-composed. That album included three classic antiwar songs that astonished the cognoscenti in folk circles and established Dylan as a formidable composer and rising star: “Blowin’ In The Wind”, “Masters Of War” and “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”

In early 1964, as the Beatles began conquering young America, the articulate and challenging Dylan occupied the minds of a slightly older set. He released two albums that year: “The Times They Are a-Changin’”, his most overtly message-oriented album; and Another Side of Bob Dylan, which represented the artist in a more introspective and personal guise with such songs as “My Back Pages” and “It Ain’t Me, Babe”.

Dylan’s gradual move from folk to rock and roll was inspired by the Beatles (whom Dylan “secretly dug”) and the Byrds (whose electrified folk-rock arrangement of Dylan’s then-unreleased “Mr. Tambourine Man” eventually went to Number One in June 1965). Dylan tested the waters with “Bringing It All Back Home”, one side of which was acoustic and the other electric. His lyrics were as demanding and literate as ever, but on songs like “Subterranean Homesick Blues” they were now set to slangy, ramshackle rock and roll. In May 1965, Dylan undertook his first tour of the U.K., toting an acoustic guitar and an often confrontational attitude. That stormy affair was documented in stark black and white by filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker in “Don’t Look Back”. Dylan returned to the States fit for battle, and the next skirmish occurred with the folk-music crowd that had so revered him. On July 25, 1965, Dylan strode onstage at the Newport Festival with an electric guitar in hand and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band backing him up. He was booed offstage after only three songs, at which point he returned with an acoustic guitar and a message for all the folk purists: “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”.

A few weeks after the Newport debacle, Dylan notched his first major hit with “Like a Rolling Stone”, a scornful six-minute epistle whose distinctively ruminative mood owes much to organist Al Kooper and guitarist Michael Bloomfield. “Like a Rolling Stone” was the opening track on Highway 61 Revisited, a landmark pop album that set Dylan’s surrealistic verse to raw, careening rock and roll. Early in 1966, he headed to Nashville to record the double album “Blonde On Blonde”, a career milestone that even Dylan allows was “the closest I ever got to the sound I hear in my mind… It’s that thin, that wild mercury sound.” Recorded in Nashville with the cream of country-music Session Men, “Blonde On Blonde” included the hit singles “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” and “I Want You”, as well as deeper, more ambitious pieces such as “Just Like a Woman”, “Visions of Johanna” and the side-long “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands”.

That spring, he embarked on a tempestuous world tour that found him backed by the Hawks (later known as The Band) and facing down audiences that still hadn’t forgiven him for “Going Electric”. On July 29, he was seriously injured in a motorcycle accident near his home in Woodstock, New York. Dylan dropped out of sight for a year and a half, rehearsing and recording with The Band at their rustic basement studio at a home (christened “Big Pink”) in nearby Saugerties while he recovered. The quaint, quirky songs from those sessions turned up on some of rock’s first bootlegs (such as “The Great White Wonder”), serving an audience that hungered for anything Dylan-related. A selection of these fascinating, low-fidelity Dylan and Band tracks saw legitimate release as “The Basement Tapes”, a double album, in 1975.

Dylan’s first post-accident release was “John Wesley Harding”, a folk-country album that found Dylan penning inscrutable parables about historical characters and outlaws as a metaphorical means of deflating the audience-hero relationship. Jimi Hendrix took one of its songs, “All Along the Watchtower”, and turned it into an electrified, apocalyptic anthem for the ages. Dylan changed course in April 1969 with his most overtly “country” record, Nashville Skyline, which found him singing engaging, accessible songs like “Lay Lady Lay” in a newly mellow voice.

Dylan generally proved less consistent on record in the Seventies, especially on such relatively minor works as “Self-Portrait” (1970), an easygoing two-disc collection that included some surprising covers (e.g., Paul Simon’s “The Boxer”) and remakes of his own songs (including “Like a Rolling Stone”) in his temporarily sweeter, cigarette-free voice; “Planet Waves” (1974), a studio album made with The Band, that came together quickly; and “Street-Legal” (1978), an album whose mystical overtones presaged the trio of more overtly biblical-themed albums that followed. There were also a number of live albums, the best of them being Before the Flood – a compelling document of his incendiary 1974 tour with The Band.

Dylan struck the mark at mid-decade with such essential recordings as Blood On the Tracks(1975), partially recorded back home in Minnesota; and Desire (1976), which contained “Hurricane”, his most trenchant protest song since the Sixties. Between the release of those albums, Dylan organized the Rolling Thunder Revue, an unwieldy but inspired caravan of troubadours and hangers-on. Dylan’s rollicking cast of characters included Rambling Jack Elliot, Allen Ginsberg, Bob Neuwirth, Joan Baez, Roger McGuinn, Joni Mitchell and Mick Ronson (late of David Bowie’s Spiders from Mars).

In 1976, Dylan provided some of the most riveting performances at The Band’s farewell concert, “The Last Waltz”, recorded at San Francisco’s Winterland. Beginning in 1979, Dylan took his most unexpected career turns by embracing fundamentalist Christianity on a trilogy of albums: “Slow Train Coming”, “Saved” and “Shot of Love”. Thereafter, he turned his attention to the state of the world, offering moralistic commentary on three albums that are the core of his work in the Eighties: “Infidels” (1983), “Empire Burlesque” (1985) and “Oh Mercy” (1989).

Bob Dylan was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1988, the same year as the Beatles. His presenter was Bruce Springsteen, who’d derived no small amount of influence from Dylan’s career. “Bob freed your mind the way Elvis freed your body,” said Springsteen. “To this day, wherever great rock music is being made, there is the shadow of Bob Dylan.”

Dylan’s career was retrospectively appraised to great effect in the boxed sets Biograph (1985) andThe Bootleg Series, Vol. 1-3 (1991). His first album of new material in the Nineties, the star-studded Under the Red Sky, included cameos from the varied likes of Stevie Ray Vaughan, Slash,George Harrison, Elton John, Bruce Hornsby and Al Kooper. Thereafter, Dylan recorded two consecutive albums – “Good As I’ve Been to You” and “World Gone Wrong” – of unadorned folk songs drawn from the public domain. In a sense, these recordings brought Dylan full circle, echoing the eponymous first album of folk songs he’d cut three decades earlier. In October 1992, Dylan’s 30th anniversary as a recording artist was recognized with a lengthy tribute concert at Madison Square Garden. Participants included Eric Clapton, George Harrison, Tom Petty, John Mellencamp, Neil Young and Stevie Wonder. Privately, Dylan himself was disinclined to celebrate former glories. “Nostalgia is death,” he remarked earlier that year to Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times.

In 1997, Dylan inaugurated a stunning late-career renaissance as a recording artist. The pace of releases slowed down, resulting in fewer but stronger albums. Although only three appeared over the course of a decade (“Time Out of Mind” (1997), “Love and Theft” (2001) and “Modern Times”(2006)), each was a certifiable classic that could stand next to Dylan’s best work. Whether atmospheric in texture, like the Daniel Lanois-produced “Time Out of Mind”, or stripped down to basics, as with Dylan’s self-produced “Love and Theft” and “Modern Times”, all three captured an artist in peak form, with much to say and in complete control of his materials. Dylan’s embedded his words in flinty, blues- and country-inflected grooves. These albums personified the term “Americana,” coined to describe a more ecumenical approach to roots music adopted by a wave of younger musicians around this time. When Modern Times debuted at Number One – representing Dylan’s first chart-topper since Desire in 1976 – the then 65-year-old singer/songwriter set a record for longest span between Number One albums by a living artist.

Dylan has spent much time on the road over the past few decades. During 1986-87, he toured with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers as his backing group, and in 1987 he did the same with the Grateful Dead (who had always been one of his strongest interpreters). In 1988, Dylan embarked on what has since been dubbed the Never Ending Tour (“NET,” for short). The seeds for Dylan’s wholehearted embrace of live performance began with a revelation during a concert in Locarno, Switzerland, on October 5, 1987. “That night, it all just came to me,” he recalled in 2002. “All of a sudden, I could sing anything.” He also gives credit to the evolving ensemble of musicians he put together. “This is the best band I’ve ever been in, I’ve ever had, man for man,” Dylan told “Rolling Stone” in 2006. “I got guys now in my band, they can whip up anything, they surprise even me.” The Never Ending Tour is said to have commenced on June 7, 1988, and Dylan has not been far from a stage in the ensuing 20 years.

Back 1964, Dylan said he hoped to carry himself like Big Joe Williams, Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly and Lightnin’ Hopkins when he was older, and indeed he has done just that. Having embraced the role of wandering troubadour, Dylan is doing what his mentor Woody Guthrie no doubt would have done, had failing health not prevented him: performing his songs for people till the end of his days.

“If you are going to go out every three years or so, like I was doing for awhile, that’s when you lose your touch,” Dylan has said. “If you are going to be a performer, you’ve got to give it your all.” And so this uniquely American legend remains alive and well, not to mention highly accessible as a performer.

In 2008, Bob Dylan’s unique contributions to American arts and letters received acknowledgement in the form of a Pulitzer Prize. The citation from the Pulitzer committee recognised his “profound impact on popular music and American culture, marked by lyrical compositions of extraordinary poetic power.”